Here’s a very short and opinionated version of recent Chinese economic history:

A bad bad no good period

China had a pretty bad time in the 19th and early 20th century. In fact, that’s an understatement - the country was more or less perpetually in a state of violence for over a hundred years. You can argue about when the period started - people point to the White Lotus Rebellion (1794–1804), the Opium Wars (1839-1860, with a break), the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) - all of these can be picked as starting points. Then, bad1 things just kept happening, including but not limited to:

Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901)

Xinhai Revolution (1911-1912)

Chinese Civil War (1927-1949)

World War II (1937-1945)

Great Leap Forward/Great Chinese Famine (1958-1962)

Cultural Revolution (1966-1976)

By the end of this period, China had some of the worst economic policies in the world: failed agricultural collectivization, communes, lack of trade, inefficient State Owned Enterprises - the lot.

“Economic Miracle” but really mean reversion

Things finally started moving in a good direction when Deng Xiaoping came to power and dismantled the failed Mao-era economic system. That marks the start of what people LOVE to call the “Chinese Economic Miracle” for reasons that evade me. Really, there was no miracle - China went from “utter failure of an economy with the worst policies in the world” to “globally average economy”. Here’s a long-term view of GDP per capita:

Basically, China did the same thing the rest of East Asia did just 20 years later because they had had an extra 20 years of madness. This chart ends in 2018, just FYI, in 2021 China slightly exceeded the world average GDP per capita but is still well below the East Asia average. Anyway, want to see what a real economic miracle looks like? See South Korea or Taiwan.

But because China’s population is so large, it had outsized impacts on the world, so people noticed and started raving about it. But again, and this is very important to internalize - China did not have a world-class brilliant government that had the best in the world economic policy2 - it just started in a really, really horrible economic place in 1978 and then got to be about average by 2021. It hasn’t jumped over the middle income trap like some of its peers.

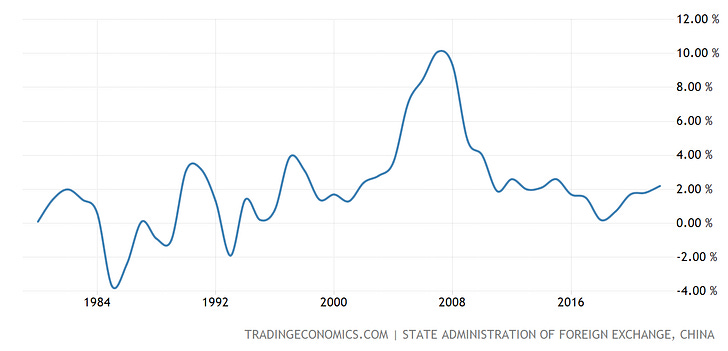

Now, conceptually, you can divide the 1978-2021 period into two stages. The first stage focused on growth through exports. That’s when everything got to be Made in China. WTO ascension put that into overdrive and the period lasted until the GFC when the Chinese current account balance peaked as a % of GDP:

The Great Financial Crisis made China look for other sources of growth. In 2012, Xi Jinping came to power, and shortly after, in 2013 he released a 60 point plan for the Chinese economy. It was a visionary document proposing sweeping reforms, and it was applauded by the Global Elites everywhere. It would open up the capital markets, get rid of currency controls, and turn China into a modern service-based Westernized economy. Here’s how a contemporary Brookings report summarized it:

Now, the plan was pretty good, but there was one minor problem with it - Xi pretty much did the opposite of what his own plan said.

What happened instead of a transition to a consumption-based internationally open economy was a transition to a government/quasi-private investment-based economy. The Chinese government decided that the country would build buildings and… Oh boy, did they build.

I’m going to show a few charts from Ken Rogoff’s Peak China Housing paper but if you have any interest in the subject, I recommend reading the whole thing.

China’s real estate investment as a % of GDP has routinely been 2X higher than that of the US at the peak of the housing bubble.

Everybody in China already owns a home.

So now, more homes are sold that are 3rd homes than first homes (!!!).

A lot of the homes are empty.

And, while housing is the big kahuna, it is by no means the only kahuna. China also built too many offices, too many steel mills, too many coal plants, too many airports, too many highways, etc.

How did China pay for all of this? Glad you asked!

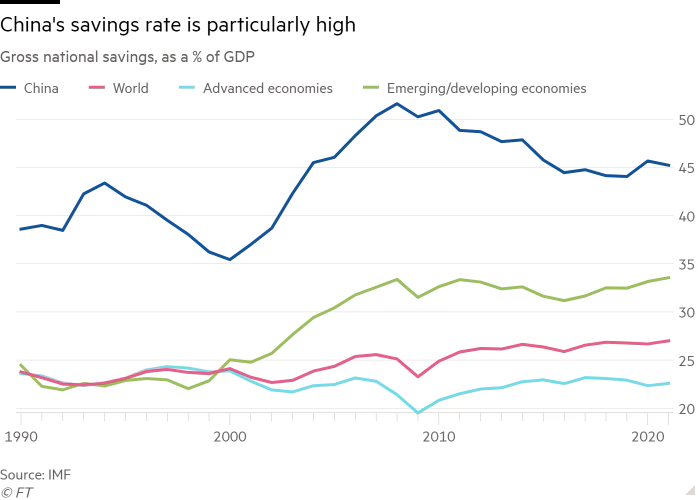

China has a WILDLY high savings rate - currently around 45%.

Now, for Chinese citizens, savings options are limited. They cannot freely convert their money to any of the major global currencies, they cannot buy shares of Apple, they can only invest within China. There are two major options to do so:

You can buy real estate.

You can buy financial assets.

So a lot of people went out and bought too much real estate, we’ve already covered that, but also, people bought a lot of financial assets. Now, the Chinese financial system is enormous and there’s no way I can cover all of it but we can look at a few things.

Firstly, there is A LOT of debt. Total debt in China is now around 280% of GDP.

To be fair, the line between Government and Corporations in China is thin and its position depends on your perspective. Let’s zoom in on two particular parts of this debt most closely tied to real estate. First, there’s the real estate developer debt - that’s fairly straightforward. Companies that build real estate borrow money to do so. A lot of building was accompanied by a lot of borrowing. The only interesting bit here is that the Chinese developers financed their building through pre-sales, so there has been a Ponzi dynamic in place.

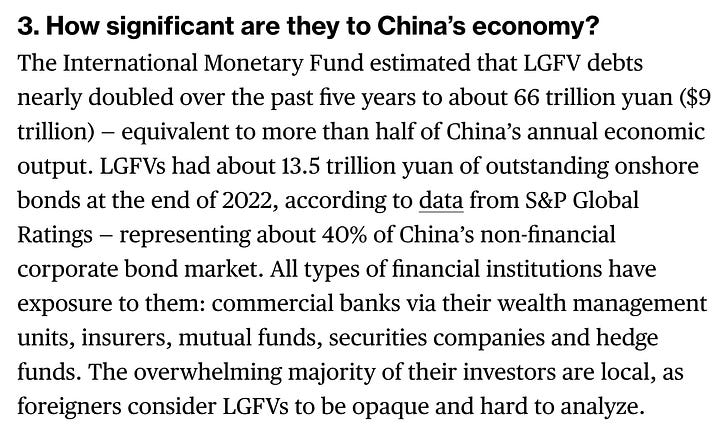

The second piece is much more interesting - Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs). Local governments in China aren’t allowed to borrow money directly from the financial markets. So they create these quasi-private companies that borrow money and use the borrowed money to build infrastructure projects - bridges and the like. They have borrowed… a lot of money.

Local governments in China own land. And historically, they’ve financed a lot of their expenditures (including those through LGFVs) through land sales and land-related tax revenue.

To sum up what we have so far: China’s growth for the past 10 years has been fuelled by real estate. It accounted for about a quarter of the economy. Enough housing was built for living in, and then a bunch more was built for savings/speculation depending on how you look at it. A lot of debt has been issued by real estate developers and local governments, and Chinese citizens (directly or indirectly) bought that debt because they are not allowed to invest outside China.

And then the whole thing imploded.

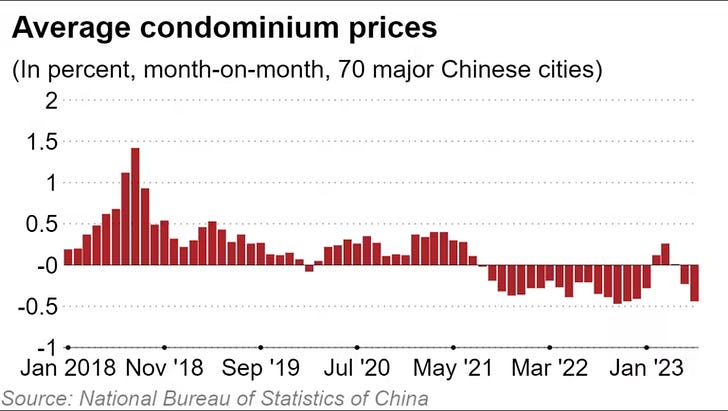

Real estate prices are falling.

Land sales have plummeted.

Real estate developers are collapsing

LGFVs are running out of cash

What will happen next? LGFVs will default/restructure. Local governments will have to drastically cut spending. For the record, local governments’ investment in infrastructure generates an estimated 14%–15% of Chinese GDP, that’s on top of the real estate being 25% of GDP. You can already see some cities shutting down hospitals, withholding wages, stopping bus services, etc.

The domino to fall after that will be the financial system. According to Grant’s Interest Rate Observer:

LGFV borrowings make up 20%–25% of total bank loans, and LGFV bonds account for 51% of all corporate bonds outstanding3.

And that doesn’t count developer loans, suppliers to the industry, etc., etc. The banking system in China cannot survive this coming tsunami of defaults.

Speaking of tsunamis, it’s time we paint a more graphic picture of what’s going to happen.

The real estate industry grinding to a halt and developers going bankrupt were the volcano eruption.

LGFVs going bankrupt will be the earthquake.

The banking system will drown, as already mentioned, in a tsunami.

That’s a lot of disasters. But did you really think this was going to end without a Mechagodzilla? Don’t be ridiculous.

The Mechagodzilla in this case is that China is running dangerously low on foreign reserves. Again, thanks to Grant’s:

The last domino to fall will be the currency. China will have to devalue its currency - we don’t know by how much, but 30% wouldn’t surprise me.

Putting it another way - China is about to experience the equivalents of the US 2008 housing bubble bursting, a Great Depression-tier banking crisis and a 1997 Asian financial crisis-type currency devaluation all at the same time.

Given how central real estate has been to the Chinese growth model, this isn’t an industry crisis. This is a crisis of the entire Chinese economic model. There will be no returning to the status quo.

Here’s a bit from Logan Wright’s testimony to the USCC (I recommend reading the whole thing):

Also:

I completely agree. I think that the idea that China’s economy is or will soon be the strongest in the world is about to be completely discredited, likely for the remainder of our lifetimes.

Now, here’s the thing. I’ve structurally been bearish on China for a long time and on a very recent episode of the Sharp China podcast (paid)

said the following (lightly edited for clarity):…every few years you get sort of the folks who've been really bearish on China for a long time, like, this is the time it's going to collapse. It's finally happening. Oh my God, I'm finally right. And the thing is, is people, I think, intellectually have been right about all the problems in Chinese economy. There are plenty of people who've been right about all the different problems and what they're facing, but so far it hasn't collapsed. And I think we're still not at the point where the economic problems are such that you're gonna see some massive crash or massive financial crisis or some sort of significant political pressure on CCP. Could be wrong, right? You know, you never say never, but it always, I think, is important to try and avoid sort of the binary boom or bust we talked about earlier. Sometimes they really can figure out how to muddle through. And especially considering … when you look at the economic problems in China, one of the things I think a lot of foreign economists, analysts, a mistake they make is they look at it like it's a Western or Japanese economic situation. And they don't talk about all the different levers and structures inside the PRC system that the party has put in place to harden the system, to maintain social stability, to force brokers, banks, many of which are state-owned or have state capital to behave in ways that the government wants to that you wouldn't necessarily see in a quote-unquote free market economy or free-ish market economy. So there are a lot of ways that there's just still a lot of pieces that the party and the government can bring to bear to keep things together. In many ways, you look at what Xi Jinping has done over the last several years, he's been much more focused on hardening the system, specifically to deal with all sorts of crises, including something like a financial crisis.

And having been called out (I’ve been structurally bearish on China since… 2016 maybe?), I decided to go on the record with some predictions, which brings us to what’s going to happen next. Now before we get there, I want to list a few beliefs I have that inform my predictions:

China generally lies in its economic data. Whatever numbers we see, the reality is worse.

The “brilliant technocrats in the CCP” thing is a myth. China’s growth has been powered mostly by mean reversion. They have… Average technocrats.

The stability of the economy is a part of the Chinese social contract. A massive loss of the population’s savings/jobs will lead to discontent.

Okay, so given that, here’s what I think will likely happen:

Continuing wave of defaults in the real estate sector and adjacent industries.

Mass LGFV debt restructuring.

Banking crisis where the equity of pretty much all banks gets wiped out.

General financial panic.

Currency devaluation.

I expect the bulk of it to happen within 24 months, and the Minsky moment to occur within that period with a 90% probability, likely sooner than later.

During COVID, I listened to the entire Revolutions podcast by Mike Duncan. It’s fantastic (though the first season is the worst, you can safely skip it). One thing that resonated with me is that Mike Duncan thinks that the French Revolution started on the 20th of August, 1786 when Charles Alexandre de Calonne told Louis XVI that the French monarchy was broke. China is about to go through an economic crisis of similar (or potentially greater) magnitude. Their youth unemployment is already over 20% and rising (and, lately, not even published). All of the ingredients for a revolution are here.

Well, guess what? the CCP really, really doesn’t want a revolution. What can they do? Note that I will skip over some technocratic policy choices like - does the federal government guarantee the municipal debts, does it guarantee banking deposits, etc. To me, they are interesting but, ultimately, unimportant. What’s important is - what can the CCP do given that their old economic model is done and there’s no going back?

There are 4 doors the CCP could theoretically take, but two of those are closed to them in practice, as far as I can tell.

The first door is to try to rely on the outside world for growth through a combination of attracting foreign investment and focusing on exports. This door is closed to them because their relationships with the major economies are at a cyclical low. In fact, the US, the biggest market in the world, is actively reducing its dependence on Chinese imports at a very rapid pace.

The second door is economic liberalization and a switch to a consumption-based economy (the 2013 plan). This door is closed to them because it would take a long time and a lot of pain. The reason you can’t do it quickly is - to jump start a consumption-based economy, you need to persuade the Chinese citizens to save less and spend more. And it’s going to be impossible to persuade them to do that when they are losing their existing savings at a rapid, rapid pace. A lot of pain over a long time would cause popular discontent. The CCP would have to increase repression - and you can’t really run economic liberalization with one hand and political repression with the other. Doesn’t work.

The third door is war. In Totalitarian Dictatorship 101 they teach you that if your economy is failing, you need to blame it on something other than poor leadership. You can’t really sell the “you’re losing your savings because we’ve mismanaged the economy” bit to your citizens. But “you’re losing your savings because it’s a necessary sacrifice to reunify China by capturing Taiwan” - that works, not to mention all the war-related jobs that would get created. I assign a 60% probability that this recession will eventually result in a war, though, as always, the timelines are hard to predict. I wouldn’t be surprised if a war was to begin at a weak point in the US political cycle, though, so 2024/early 2025 makes sense but my level of confidence in this prediction is not very high.

The fourth door is the CCP booting Xi out of power and blaming him for the recession. That might work but isn’t guaranteed to work. Given how successfully Xi has consolidated power over his rule, I do not find this too likely but I will be the first one to admit that internal CCP dynamics are completely opaque to me.

The last possible scenario for the CCP isn’t a door they can walk through, but a window to get thrown out of. It’s possible that nothing the CCP does will save the regime. The dynamics of discontent in China is hard to judge from the outside but the CCP has invested a lot in mechanisms of repression, so I think this is unlikely to occur before the CCP tries the war option.

That was a lot of writing, and I’ll stop here. But if there’s any interest, I can write another piece on what the global economic/financial repercussions of a Chinese megacrisis might be. Let me know!

I’m not making a political point about any of them here, just noting that there was a lot of death and violence. Actually, scratch that, The Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution were two of the worst self-inflicted wounds by anyone in world history ever.

To be fair, there was some finesse in the 1980s, moving from a five-year-plan to a market-ish economy without your government falling is tricky.

An observant reader might notice that a source above cited 40% for the same number. What can I say, China is a black box, estimating things is hard.

Very detailed analysis and I appreciate the mention of your bias as a forecaster of demise several years ago. The hyper links to reference material is helpful as well. My concern is the likelihood of confrontation including war. While I am sure the CCP would like to see the economy rebound to maintain economic power, I believe the investment in war materiel will lead to its use. Of course it will be used because of the containment attempts of the West or another such excuse, especially if the economy falters at a more rapid pace. Please continue writing on this topic and thank you.

I'm by no means an economist, but I've noticed one thing: the Chinese government has spent the last two years-ish increasing its hard-knuckled control over corporate entities industries and services it deems notably profitable; might they not just use the profits they can extract from those by various means to prop up or mitigate other sector failures? Also, controlling the legal system means controlling contract law; which gives them control of the collection and structure of all debt. The government could force restructuring of any debt in any sector they want under threat of outright cancelation of that debt; and creditors would have no other legal recourse. This, in tandem with restrictions on capital flight already in place, could prevent a large-scale collapse in a sector by channeling it into a bunch of medium-term, time- released smaller ones.

Those are traumatic too; but lack the contagion-effect that creates general collapses.